Fears of the Framers

"The Trouble With Elections: Everything We Thought We Knew About Democracy is Wrong," Chapter 1.2

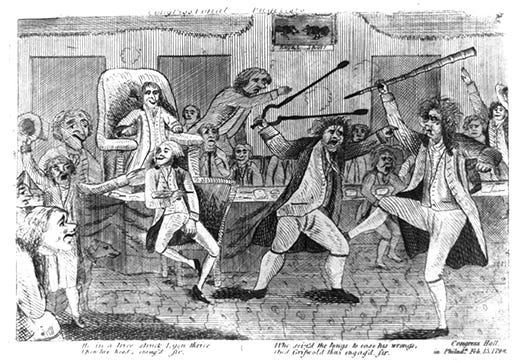

a 1798 political cartoon depicting a ‘debate’ in Congress between Democratic-Republican Matthew Lyon and Federalist Roger Griswold.

The depressing traits of American electoral democracy discussed here are frequently treated by commentators as if they were new, or at least far worse than in the past. But the inherent trouble with elections was already recognized by people like James Madison (often called the "Father of the Constitution") prior to the Constitution's adoption. In a 1787 essay setting forth the failings of the Articles of Confederation, entitled "Vices of the Political System of the United States," Madison presented this troubling dynamic of elective representation:

"Representative appointments are sought from 3 motives: 1. Ambition 2. Personal interest 3. Public good. Unhappily the two first are proved by experience to be most prevalent. Hence the candidates who feel them, particularly, the second, are most industrious, and most successful in pursuing their object: and forming often a majority in the legislative Councils, with interested views, contrary to the interest, and views, of their Constituents, join in a perfidious sacrifice of the latter to the former. A succeeding election, it might be supposed, would displace the offenders, and repair the mischief. But how easily are base and selfish measures, masked by pretexts of public good and apparent expediency? How frequently will a repetition of the same arts and industry which succeeded in the first instance, again prevail on the unwary to misplace their confidence?”

As I will discuss in subsequent posts, Madison also worried about factions. He hoped to dilute this problem to some extent by sheer force of size; he figured that a vast nation would have so many competing interests that no one faction could come to dominate. With divergent regional interests and communication links that took weeks, he assumed consolidation of factions would be impractical, if not impossible. But this turned out not to be the case. The dynamics of competitive elections quickly caused these dreaded factions to coalesce in the form of national political parties – with their attendant partisan rancor. Ironically, Madison himself helped found one of the first political parties in the new republic.

The partisan political system we have, in which two dominant parties maintain a duopoly over all levels of government, is exactly what many of our founders feared most for their republic. John Adams, in a 1780 letter to his friend Jonathan Jackson discussing the soon-to-be-released Constitution of the state of Massachusetts, stated that:

"There is nothing which I dread so much as a division of the republic into two great parties, each arranged under its leader, and concerting measures in opposition to each other. This, in my humble apprehension, is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil under our Constitution.”

George Washington also warned about partisanship in his 1796 Farewell Address to the nation:

"The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries, which result, gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of Public Liberty."

The feared partisanship blossomed almost immediately with the rise of the Federalists, aligned with Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, aligned with Madison and Jefferson. Although it may seem new to observers today, who look to the unusual level of bipartisanship of the 1950's and 1960's as if it were the norm, hyper-partisanship has been the reality in American politics practically from the beginning, with only relatively brief interludes of civility. In 1800 the Federalist Connecticut Courant warned that if Thomas Jefferson became president "Murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of the distressed, the soil will be soaked with blood, and the nation black with crimes."

The tendency for politicians to sidestep tough issues is also not new. The Framers of the Constitution found it expedient to simply defer certain issues to future generations. In order to facilitate the replacement of the Articles of Confederation and bring all thirteen states into the "more perfect" union they envisioned, they intentionally avoided the issue of slavery, leaving the resolution of the divisive issue to a later time. Indeed, they even placed a time-lock within Article V, which deals with the process of amending the Constitution, expressly prohibiting any amendment to the clause that allowed the continued importation of slaves, until 1808 at the earliest. Pragmatic postponement of the slavery issue planted the seeds for a later bloody civil war.

It’s clear that American democracy, and western democracy in general, hasn’t quite lived up to the ideal, yet support for that ideal has nevertheless spread across the globe over the past two centuries. However, a joint Harvard/University of Melbourne study in 2017 suggests that trend has reversed. By drawing on data from the European and World Values Surveys, researchers Roberto Foa and Yascha Mounk found there has been a precipitous decline in public commitment to democracy (interpreted as systems based on competitive elections). They refer to this phenomenon as ‘democratic deconsolidation.’

In well-established electoral democracies, such as the United States, Britain, and Australia, the percentage of people who say they feel it is "essential" to live in a democracy has steadily dropped since World War II from roughly 75 percent down to just over 25 percent by the time of the study. While not as precipitous, this diminution is even occurring in famously liberal countries such as Sweden and the Netherlands. Widespread disdain for democracies’ “establishment politicians" is a global if not universal phenomenon.

It is my assertion that the election of the non-politician Donald Trump in the United States was largely a result of that growing public sentiment. An analysis released by the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge in 2020 confirms that dissatisfaction is the underlying cause. Researchers compiled a new dataset combining more than 25 data sources, 3,500 country surveys, and 4 million respondents between 1973 and 2020 asking citizens whether they are satisfied or dissatisfied with democracy in their countries. The authors wrote, "We find that dissatisfaction with democracy has risen over time, and is reaching an all time global high, in particular in developed democracies." By 2020 the percentage of residents in electoral democracies who reported that they were dissatisfied with democracy in their own country reached 57.5 percent. Between the 1990s and today, dissatisfaction with democracy in the United States has fluctuated, but overall had the sharpest rise of any country surveyed.

So is there a remedy? There may well be. But the optimal path to a better democracy is not merely through improving elections, which most reformers assume is the only way forward. In normal parlance, democracy and elections have become synonymous (though, as we will see, this wasn't originally the case). After all, elections are seen as the quintessential means for holding leaders accountable. "Free and fair elections" are almost universally considered the cornerstone of representative democracy. But could elections themselves be causing the problem?

This book is about the numerous inherent democratic defects of elections, and how we might build a better democracy without exclusively relying on them. It is difficult to recognize what things we "take for granted" simply because we know nothing else but what exists. As the saying goes, "fish would be the last to discover water." The notion that fixing democracy is just a question of fixing the electoral process is an assumption we must question. But in order to move forward, it is essential to first determine in which direction we should go. Where is democracy's North Star?

Future posts will systematically set out the case that democracy's North Star is sortition. Today a little-known term, this concept was fundamental to the earliest democracies, and may be the salvation of modern democracy as well.

In the last paragraph, “sets” should be “set”.

I think that equating democracy with competitive elections is the issue. I think democracy is something on a different level. Similar to the relationship between science and technology. Democracy is to science as elections are to technology. Elections try to implement democracy, as technology tries to implement science. In both cases, different things can be tried to implement the principles involved. In democracy, I think the main principle is that the people are ruling themselves. I don’t know whether freedom and liberty are involved too, but may be. Is there a standard philosophical definition of democracy?

"Most observers agree that the election of the non-politician Donald Trump in the United States was largely a result of that growing public sentiment."

Citation? Who is (or counts as) "most observers"? If this cannot be supported, you might want to consider rewording to something like "it is reasonable to conclude that..."