Voter Decisions

From "The Trouble With Elections: Everything We Thought We Knew About Democracy is Wrong," Chapter 8.5

The previous post focused on the behavior of partisan voters. But what about non-partisan voters who say they “vote for the person not the party?”

One might hope that informed, rational thought was in the driver’s seat when it comes to deciding how to vote. This does not appear to be the case most of the time. Some may argue that rational ignorance is not as big of an obstacle as I have made out, because many voters become virtually informed, by offloading the time-consuming effort onto some trusted surrogate or organization. The voter might look at lists of endorsed candidates by the League of Conservation Voters, or the NRA, the Chamber of Commerce, their union, church leader, or simply Uncle Luke (who pays attention to politics). However, a recent study found that voters widely misinterpret candidate endorsements from special interest groups, frequently drawing the opposite understanding by incorrectly assuming an organization agrees with the voter’s policy preferences, when in fact they are at odds. In other words such off-boarding to surrogates has a high likelihood of failing for all but a few well-known special interests. Further, this decision to defer to some particular “better informed” person or organization is itself usually an emotionally-based, and rarely a carefully considered choice that weighed all the other options. It is still based in rational ignorance, simply one place removed.

We all tend to suffer from what psychologists call naïve realism. This is the tendency to believe that we see the world objectively, and that those who disagree with us about policy or other matters must be uninformed, irrational, or biased. Undergirding and expanding on this predisposition is the illusion of information adequacy. Experiments have shown that

“people tacitly assume that they have adequate information to understand a situation and make decisions accordingly. Yet, individuals often have no way of knowing what they don’t know.”

The researchers explained the dynamic this way:

“For example, many drivers have pulled up behind a first car at a stop sign only to get annoyed when that car fails to proceed when traffic lulls at the intersection. Drivers of these second cars may assume they possess ample information to justify honking. Yet, as soon as a mother pushing her stroller across the intersection emerges from beyond their field of vision, it becomes clear that they lacked crucial information which the first driver possessed.”

While voters almost inevitably suffer from this cognitive bias, the learning phase of a citizens’ assembly can readily overcome it.

But the problem of voter decision-making goes much deeper. Several studies suggest that the voter decision-making process has less to do with rational thought than many people presume. In 2005 Alex Todorov and colleagues at Princeton found that when they showed people photographs of candidates for U.S. Congress or Governor (who participants were unfamiliar with), for less than one second each, and then asked them to rate the faces in terms of which one looked more “competent,” the participants’ flash assessments predicted the actual winners nearly 70 percent of the time, far more than the 50 - 50 expectation of chance alone. This finding has been replicated many times. Two Swiss researchers on the faculty of Business and Economics at the University of Lausanne, had two separate groups, one Swiss adults and one children, look at pairs of candidate photos, and pick which they thought looked more honest. To make sure the participants wouldn’t have any knowledge of the candidates, they used candidates from another country. They used official candidate photographs from French parliamentary elections. They further avoided using photos of “unelectable” candidate faces (whether due to ethnic bias, ugliness, or whatever), by limiting their pool of candidates to races in which a challenger had defeated an incumbent, thus assuring that either face could win an election, since both had at some point. The choices by both the adults and the children matched the actual winner of each election contest over 70 percent of the time. This indicates that a superficial factor, which the French voters would probably deny played any part in their decision (like the French and German wine buyers discussed earlier), may in fact have tipped the balance in the election process.

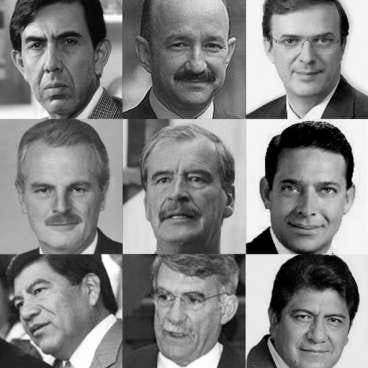

The influence of candidate appearance on election outcomes may be pervasive. MIT researchers replicated the results using candidates from Brazil and Mexico,

while asking voters in the United States and India which candidates would make better elected officials. Gabriel Lenz, a co-author of this study, reported that

“We were a little shocked that people in the United States and India so easily predicted the outcomes of elections in Mexico and Brazil based only on brief exposure to the candidates’ faces.”

Recent research by Rodrigo Praino and Daniel Stockemer suggested this candidate “attractiveness premium” is most impactful in single-seat winner-take all elections, which are standard in the United States, and in low-information races where voters know relatively less about the candidates. They also found that the effect is substantially neutralized in party list proportional representation elections, which de-emphasize the characteristics of individual candidates. Other research, based on laboratory experiments as well as actual elections, showed that voters tend to favor candidates with lower voices, although, in a separate study they found no evidence that people with lower voices are more effective as leaders.

It is conceivable that voters are picking up on something valid about candidates from their face or voice that actually does make for better leaders. So, researchers checked this too. A 2018 study found that although voters are swayed by candidate appearance and perceptions of candidate personalities, these superficial impressions completely failed to predict whether these candidates would be effective if elected to office. The researchers asked 138 local politicians in the UK to rate their own personality, and also asked 755 of their colleagues to anonymously rate their performance in office. They also had 526 people look at photographs of the councilors and surmise about their personalities. The researchers then compared these personality profiles and ratings of appearance to the politicians' share of the vote in re-elections, as well as their evaluated performance. Candidates whose appearance was described as competent did better in the elections, but were not deemed by their colleagues to be any more effective in office.

This certainly doesn’t mean that most voters decide who to vote for based on split-second intuition they infer from appearance. Not surprisingly, further research has found such effects to be strongest among less-well informed voters who watch a lot of television. Some voters rely on party labels, or even a careful analysis of candidates’ stands on certain issues. But enough voters, especially in close races, apparently use these quick gut reactions to swing the outcome one way or the other. Vast amounts of psychological research suggests that people then rationalize their selection with plausible “reasons” to help convince themselves that they voted responsibly.

It seems unlikely that our instant gut assessment of candidates’ faces is a good method of choosing political leaders, and nobody publicly embraces that belief. But all the evidence indicates many voters are relying on such quick system one thinking, instead of laborious system two reasoning. The 2016 presidential campaign of Donald Trump is an interesting example. Most voters knew at least a bit about the person as a wealthy businessman and TV celebrity, and most had an instant gut reaction to his becoming a candidate — either drawn to what they perceived to be self-confident leadership willing to take on a corrupt establishment, or repulsed by what they felt was narcissistic bravado. The continued support for Trump by his “base” throughout his presidency and beyond, and/or the disdain by his opponents, may be attributable to what psychologists refer to as confirmation bias and the Einstellung effect, in which we can be effectively blinded to, or misinterpret, new information, due to previous information and beliefs.

It also turns out that voters informing themselves by reading the newspaper, watching TV news, scanning the Internet, etc., to keep up on public issues does not make these voters better able to evaluate candidates. A study led by Brendan Nyhan of Dartmouth found that those with a favorable opinion about a particular political figure, and who also had more political knowledge (in that they followed the news, etc.), were more immune to factual corrections, which contradicted their bias, than were people who also had a favorable view of the person but were less “well informed.” In fact the factual corrections tended to harden the erroneous beliefs of the “better informed” participants, as a sort of defense mechanism. Thus, even balanced presentations, depending on the messengers, may not lead to a common understanding of reality by voters, as each chooses which facts to accept and which to reject. Research has shown that political misperceptions, with motivated reasoning and psychological resistance to factual correction, are fundamental stumbling blocks for electoral systems. Importantly, the learning and deliberation processes used in citizens’ assemblies appear to mitigate this effect.

The psychological infirmities of the electoral method of choosing political decision makers goes far deeper and are far more troubling than how they affect voters. The psychological and other distortions of the competitive election process on legislators and society as a whole are even more disturbing. What sorts of people choose to run for office? What sorts of people would never consider it? Even when politicians are not corrupt, or beholden to special interests, how does the competitive partisan environment affect legislators’ ability to absorb information, deliberate, and make good decisions? How does the feeling of power they experience change their ethical judgments? I will examine these and many other problems in the next chapter.

For me, in local elections where I don’t know the candidate or ballot measure well enough, I go by endorsements and political contributions, or ask friends. I don’t trust the campaigns, the news, or even the voters pamphlet (because it only has statements from the candidates and/or from folks with an interest in the election). I’ve been k own to vote for a woman over a man if I know neither. Lately, I’ve pretty much given up on voting due to many of the problems you bring up. On a national scale, it’s absurd.

“...attractiveness premium” is most impactful in single-seat winner-take all elections, which are standard in the United States, and in low-information races where candidates know relatively less about the candidates.” In this sentence, near the end, “candidates know very...” should be “voters know very...”