The Modern Revival of Sortition

From "The Trouble With Elections: Everything We Thought We Knew About Democracy is Wrong," Chapter 14.1

From the earliest days of elected representative government, problems associated with elections have been readily apparent. In both England and the United States, candidates commonly passed out intoxicating spirits or meals to buy votes. Indeed, the disgust about the tumult and corruption of election campaigns prompted one anonymous subscriber to the English journal The Political Register and Impartial Review of New Books in 1768 to propose a “Scheme of a Political Lottery, for the Peace of the Kingdom” (presumably tongue in cheek). The author proposed that elections for parliament be replaced by a lottery. Lottery tickets would be sold, with the winners getting seats in parliament. Five percent of proceeds would be set aside to buy “guzzle” for all the boroughs, with the remainder going to pay off the national debt;

“by which scheme the noisy and expensive business of electioneering (which puts the whole kingdom in a ferment) will be over in two hours, many people have an opportunity of serving their country cheap, and much bribery and corruption prevented.”

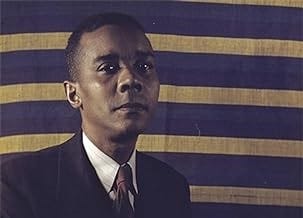

Despite their glaring flaws, elections came to be thought of as the only alternative to authoritarianism. Sortition was still used in some Italian city republics, but as an anti-corruption tool among the elite ruling families – not for popular democracy. By the early eighteenth century democratic sortition had evaporated from both the public’s and political theorists’ consciousness. For nearly two centuries hardly any published proposals for sortition appeared. The first serious essay I know of in the twentieth century1 was by the Trinidadian anti-Stalinist Marxist and historian, C. L. R. James in 1956 entitled “Every Cook Can Govern: A Study of Democracy in Ancient Greece; Its Meaning for Today.”

In recent years, however, advocacy and real-world implementations of sortition have been mushrooming around the globe. In this chapter I will look at a few of these. They range from unofficial advisory “deliberative polls,” to formal public policy decision-making bodies. A number of sortition theorists started experimenting with real-world applications towards the end of the twentieth century. The modern reinvention of sortition can be traced to several parallel developments in Europe and North America.

German Prof. Dr. Peter C. Dienel in 1972 developed what are called “Planning Cells,” to better connect average citizens with government decision-making. A random sample of 25 people directly or indirectly affected by some policy issue are paid to study an issue and deliberate over a five to seven day period. They are provided with background material, and then gathered to listen to presentations from experts and various competing advocates. The participants then break into small groups for discussion. At the end of the process, the planning cell adopts final policy recommendations. These planning cells are typically convened by governmental entities that are willing to adhere to the recommendations that come out of the process, and participants are generally very engaged and pleased with the deliberative process. First employed in the town of Schwelm, in the Ruhr District of Germany, planning cells have since been used more than a hundred times in Germany, Spain and even the United States.

A similar model has been employed in Austria through what are called “Wisdom Councils.” The Office of Future Related Issues (OFRI) in the State of Vorarlberg, Austria has facilitated local governments in convening dozens of Wisdom Councils. These are randomly selected groups of 12 to 15 residents who tackle an issue of their choosing, using facilitation in an attempt to reach a consensus position. In some cases issues are pre-selected by government officials, in which case they are referred to as “Creative Insight Councils.”

In the United States, Ned Crosby, apparently unaware of this German invention, founded the Jefferson Center in 1974 to facilitate the development of a similar model he called a “Citizens Jury.” This is variously spelled as “Citizen Jury,” “Citizens’ Jury,” and “Citizens Jury,” the last of which was trademarked by the Jefferson Center. Pulling together a random sample of average citizens, various Citizen Juries, initially in Minnesota and in later decades across the country, tackled a variety of thorny issues such as health care reform, presidential elections, agricultural impacts on water quality, physician-assisted suicide, global climate change, etc. The goal was to see if a deliberative process in which participants heard all sides could uncover common ground and discover a sort of group wisdom. The juries were generally small (a dozen or more participants), but were often conducted multiple times to gauge the consistency of decisions. Both participants and organizers were happy with the process and outcomes. But these were essentially academic exercises demonstrating the validity of the deliberative model, rather than having an actual impact on public policy.

A few books began to appear with proposals for selecting at least some legislators by lot, including Un-Vote for a New America in 1976. and A Citizen Legislature by Ernest Callenbach and Michael Phillips in 1985. The renowned political scientist Robert Dahl proposed a sortition body to enhance democracy, which he called a “minipopulus.” Dahl, who was called the “dean of American political scientists,” by Foreign Affairs magazine, in the conclusion of his important book, Democracy and its Critics, proposed sortition to create a set of deliberative bodies (what he termed a “minipopulus”) each dealing with a defined issue area, as a possibility for a future democracy. In his proposal a minipopulus would complement, rather than replace conventional democratic institutions. Each minipopulus could be attended by “an advisory committee of scholars and specialists and by an administrative staff. It could hold hearings, commission research, and engage in debate and discussion” for perhaps a year before rendering a judgment. By creating a microcosm of the full citizenry through sortition, as in the case of jury service, the participants suddenly have an interest in becoming informed and attentive because there is a substantial possibility that their vote, or their contribution to debate, will actually matter.

The sortition model that has become the predominant design in the early twenty-first century is known as the citizens’ assembly. It was launched in 2004 in British Columbia, Canada when the provincial government appointed Dr. Jack Blaney to chair and coordinate the creation of a representative body of non-politicians to examine and propose any needed reforms to the province’s election system. I will describe this historic launch and model in some detail in the next post, and then continue with a survey of the variety of sortition designs promulgated shortly thereafter.

A humorous article by the journalist and satirist H. L. Mencken. entitled “A Purge of Legislatures,” which proposed a lottery system, appeared in 1926.